Biography~Biogrāfija

Latvian text/ Latvijas teksta -Aleksandrs Karpovs – latviešu mākslinieks un cīnītājs: Biogrāfija

Slide show presentation at Mark Rothko Art Center in Daugavpils (June-July 2014)

Aleksandrs Karpovs: Artist and Warrior

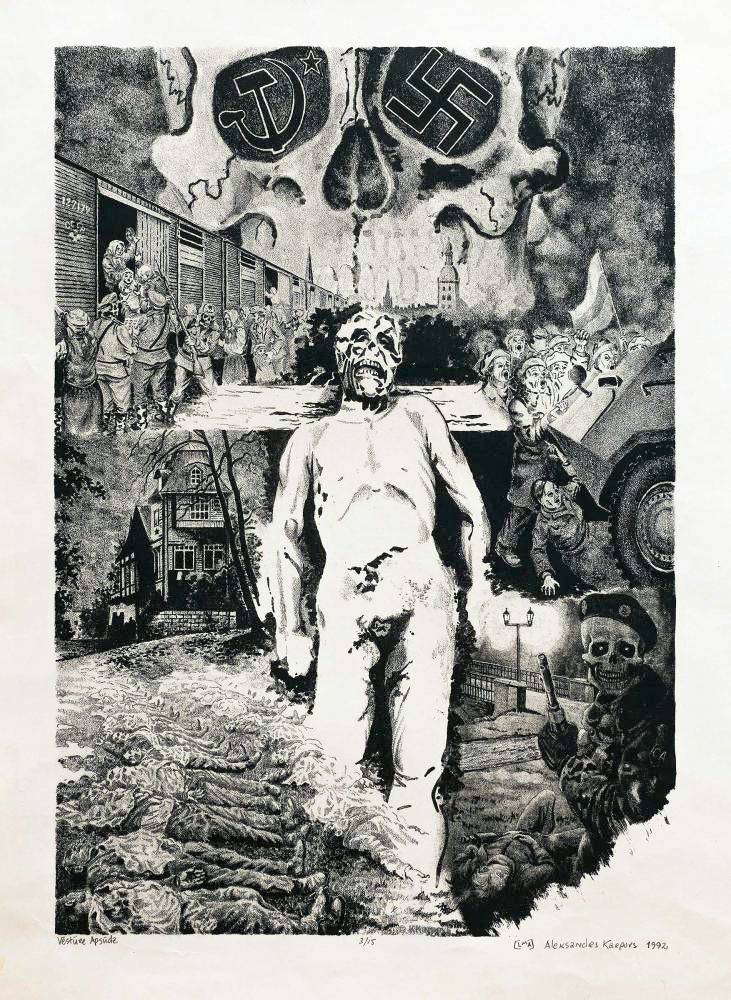

Aleksandrs Karpovs was a gifted graphic artist who devoted his talent and ultimately gave his life to help free Latvia from the Soviet occupiers. He used social realism in both America and Latvia as his “weapon of choice,” to confront the forces of evil in both countries. In America he used his art to confront materialism, racism, police brutality, war, and pollution. In Latvia he depicted Soviet crimes of destroying the culture, murdering innocents, and ultimately acts of genocide. He also showed the beauty of the Latvian architecture and monuments to remind those exiled abroad.

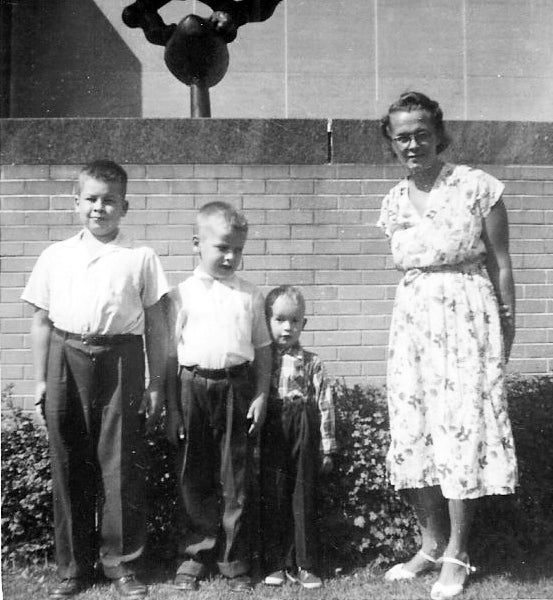

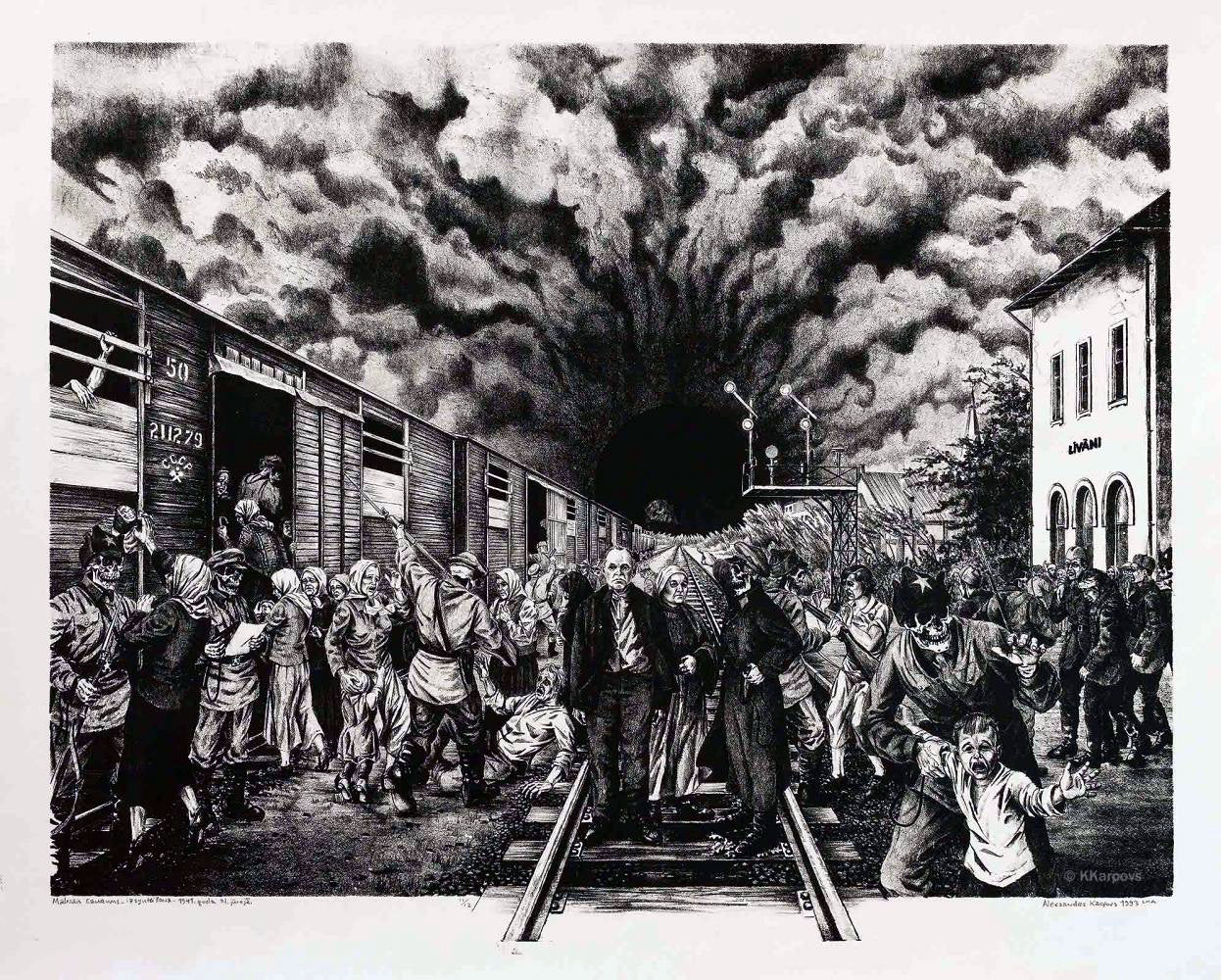

Aleksandrs was born in Des Moines, Iowa (USA) on March 21, 1953 with Latvian as his first language and culture. His mother, Lūcija, was fortunate to have escaped Stalin’s genocide of her family during the first mass deportation of June 14, 1941. Her father and mother (Justyns and Stefānija Volonts) were herded onto separate cattle cars in Līvāni for a one-way trip to separate parts of Siberia. Her sister, Regina, had also been deported on June 14, 1941, but from Riga where she was living as a student with her uncle, Jānis Volonts, (Latvia’s Minister of Welfare) and two cousins, Ada and Margarita.

Lūcija’s tragic losses did not end in Latvia. She fled to a German refugee camp, along with her sister Helena. There she met and married Anatolijs Karpov in the German camp of Fulda in 1946. They ended up emigrating to Minneapolis, Minnesota (USA) with their three children. He later divorced her, for a younger woman, nine years later. Lūcija was left destitute, not yet able to speak English, with three boys to feed and bring up alone in America.

Latvian language and culture was included in the community of Latvian Catholics in Minnesota who had also escaped Soviet occupation. Many Latvians in Latvia who lived through the occupation, to this day, do not understand hardships suffered by some of those who survived the genocide in foreign lands. Nor could they comprehend the suffering in Siberia given ongoing Soviet propaganda. On the other hand, those in the U.S. knew how much worse it was for the relatives in Siberia. Aleksandrs' grandfather had died in August, 1941 within two months of his arrest. Lucija would often go hungry so that her family could survive. She would send care packages of cheese, butter, and sugar to her mother, Stefānija, and sister, Regina, in Siberia via the Swiss embassy.

Lūcija, never recovered from her losses under the Soviets and subsequent betrayal by her husband. While she was one of the most generous and compassionate persons, she was broken by her experience. She died of cancer in 1965, at the age of 51. Aleksandrs’ life in the U.S. after his mother’s death was not easy. He had lost his mother and brothers at the age of 13, subsequently lived with five separate foster families until he was considered old enough to be on his own at 18. His eldest brother, Juris, died in 1977 in a tragic car accident in New Orleans. Juris was only 31 years old. His wife Janet and their two children, Anatole and Aleksanders, survived the crash. Konstantīns Karpovs, his other brother, endured one foster family until he was 17. He was then fortunate enough to meet his future wife, Michele. They settled in Northern California with their two children, Aleksandra and Andre.

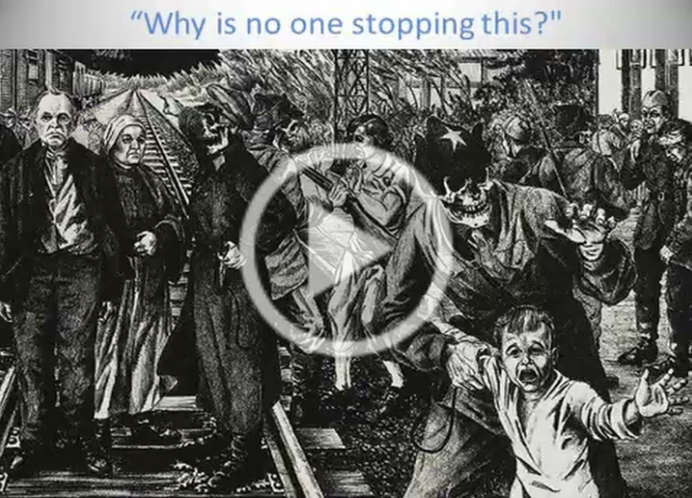

The experience of these losses and poverty in America greatly influenced Aleksandrs’ pursuit of a career as a socially conscious artist with a focus on printmaking (lithography and etching). Artists of social conscious art tradition shun the notion of “art for arts’ sake.” By creating images of social injustice and political struggle through the printmaking techniques, this enables millions to view their message of protests and help bring about social change. The socially conscious artist manipulates materials and technique for “life’s sake.” Aleksandrs worked in a hospital for 20 years among the poorest in Minnesota to finance his art education and give something back to the suffering in America: “During my employment there, I witnessed firsthand the stark reality of just how sick American society had become. The shocking sights and sounds of the victims of poverty, the physical deterioration such a condition has on a human being, gave me a glimpse of the broad extent of the injustice of this society.”

In the early 1970s a racist police vigilante program in Detroit known as S.T.R.E.S.S. (Stop the Robberies and Enjoy Safe Streets) terrorized the African American community. Aleksandrs referred to this as, “institutionalized racism at its worst…I became very aware of the effects of Reagan’s indifferent government toward the plight of the poor by the continuous increase in numbers of the sick and injured coming to the emergency department. I became increasingly frustrated as I became aware that I was treating only the wounds inflicted by this unjust society and not the ‘cause.’ I came to the realization that the most effective weapon I have to effect real change was my talent as an artist, with this in mind I returned to the arts in 1986 with renewed energy and determination.”

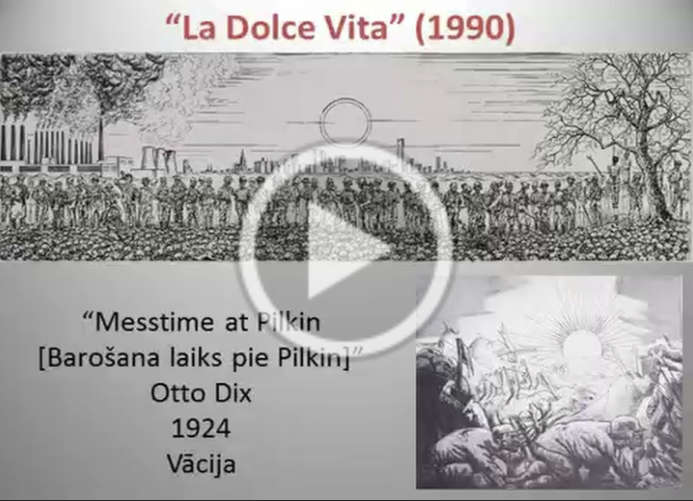

From 1986 – 1990, along with subdued social realism, Aleksandrs’ art showed the beauty of Latvian cities Cēsis, Rīga, Rēzekne and Daugavpils. These prints were also intended to raise the consciousness of the American public of the very existence of Latvia. This became more important in 1988 when Latvia began to make stirrings to reestablish its independence from Soviet occupation. “If the sale of my prints of Latvia were any indication, I was very successful in accomplishing an awareness in the American public of the plight of Latvia and its struggle for freedom.”

Aleksandrs was well-known among local Latvians and some of his works were sold to the Latvian house in Minneapolis. Latvians abroad knew very well that their venues were frequented by Soviet government informers and that anti-Soviet actions may endanger their chance to get visas to visit the occupied country. Moreover, it might endanger their relatives who were living there.

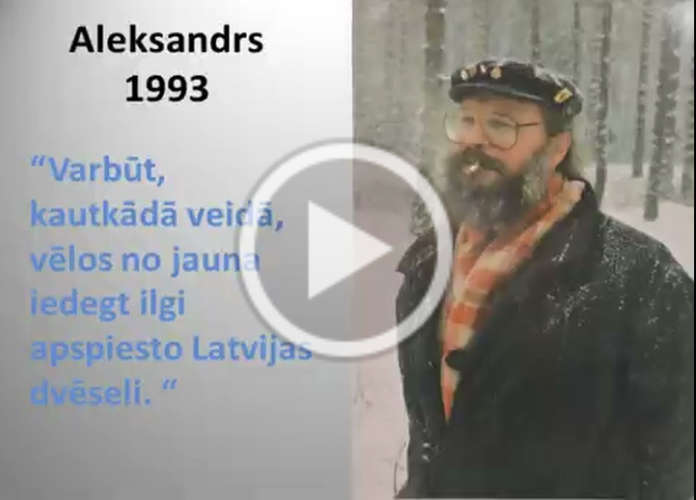

Aleksandrs completed a Bachelors of Fine Arts with high honors at the University of Minnesota in 1990, followed by a Masters of Fine Arts in Latvia in 1993. Later he taught printmaking at an art college in Rēzekne, Latvia. He inspired his students to pursue the field of social realism. He wrote in his thesis: “Behind the glitter and mass media controlled consumer society there exists an ugly side of American society which begs to be brought to the fore. I dedicated my life and talent to this cause for social justice in America. Not merely satisfied with some kind of social reform, I used my talent as a weapon for revolution. My images went straight for the throat and attacked this ‘other’ evil empire with all my passion and soul. My prints are meant to shock the viewer; there is no symbolism or metaphor to obscure my message. Realistically rendered, these images of social injustice are very real and must be presented as such in all its ugliness. I want my images to be understood for what they are, a visual act of dissent.”

In a real sense Aleksandrs used art as a weapon in Latvia to fight Soviet occupation to defend his country. He considered that the main obstacle in the life and development of democratic societies is fascism: “Brown or red – they will not escape my images with their crimes against humanity.” He created a visual record so history could accuse the perpetrators of genocide and never forget the truth.

Aleksandrs also participated in demonstrations and provided his art to newspapers exposing Soviet atrocities, risking his life to support the effort of Latvians to free themselves from the occupiers. He was twice beat up and hospitalized with a concussion. Attackers were, as he called them, the “red fascists.” One month before his death, he sent a letter to his brother, Konstantins, jokingly suggesting he may have to leave town as local Russians in Rēzekne had been beating on his door at night with death threats following a local showing of his artwork. His letter became serious when he described his wish to be buried with a Latvian flag over his coffin. On March 22, 1994, Aleksandrs’ body was found in the corridor next to his room. The circumstances surrounding his death remain a mystery, though officially are due to natural causes. Days later his room was found ransacked, with documents and papers strewn all over the floor. Hidden under his bed attached to the springs was the plate of his final lithograph (“Mūsu Rīga”/“Our Rīga”). Also found was the deed to his grandfather's, Justyns Volonts, farm and forest; and Justyn's passport, which was used for his family to obtain citizenship and ownership of the property. This land had earned Justyns, his wife Stefānija, and daughter Regina one-way ‘tickets’ in cattle cars to Siberia during the first mass deportation of 15,424 Latvians (8,259 men and 7,165 women) on June 14, 1941 (State Archives of Latvia 2001). Aleksandrs Karpovs, a Latvian patriot, was buried with a Latvian flag draped over his coffin. Today, his remaining brother, Konstantins, and Aleksandrs' nieces and nephews, are the proud advocates of Latvian culture and history.